On Wednesday May 18, the Evictions Memory Museum opened in Vila Autódromo, the favela which has become world famous for standing up to Olympic development in Rio de Janeiro. Thanks to their fierce resistance, those who hadn’t yet left recently won a landmark deal to be allowed to stay in their community–the first collectively signed relocation agreement in favela history. While their houses will be destroyed, the residents who remained will have new houses built by the City, in time for the Olympics. While community activist Maria da Penha accepts that the deal isn’t a “complete victory,” she is happy with the deal that the City has arrived at with residents, as she will have a new home in the community, which she has always stressed is her right.

Under the new deal, which is far removed from what residents wanted for the community, as documented in their People’s Plan, 25 new homes will be built along one street. The church will be able to stay, but every other building will be destroyed. Two schools will be built in the community, although residents never asked even for one, with Maria da Penha condemning this as a “false legacy,” suggesting the purpose is simply to give the impression the City is providing services. Given the lack of desire for these schools, the money used to build them would probably better be used to ease the current issues with schooling across the state of Rio.

The new homes are slated to be delivered before the Games on July 22, giving the City just over two months to build all the homes, leaving little room for error before the Olympic opening ceremony on August 5. While completing the project in this time frame would be an impressive feat of engineering, it is more likely that contractors will make short cuts and the homes delivered to residents will be low quality construction.

The new homes will be professionally built, throwing Vila Autódromo’s status as a favela into doubt (definitions vary, but favelas can be partly defined as communities built by residents themselves). So much will change that the term renewal is more accurate than upgrades. It is as if the City wants to wipe the slate clean and start again, rebuilding Vila Autódromo in a way that fits with the surrounding condominiums of Barra da Tijuca. According to Maria da Penha, during the negotiations over the deal the City even tried to change the name from the “Vila Autódromo Community” to “Vila Autódromo Condominium.” Along with the new building style, this fits with residents’ long-held beliefs that they are being evicted as part of a process of urban renewal. After the demolition of three homes behind the Neighborhood Association in February 2016, Maria da Penha said the demolitions were happening to remove the “ugly” favela and create a “beautiful place” for those staying at the nearby Olympic hotel.

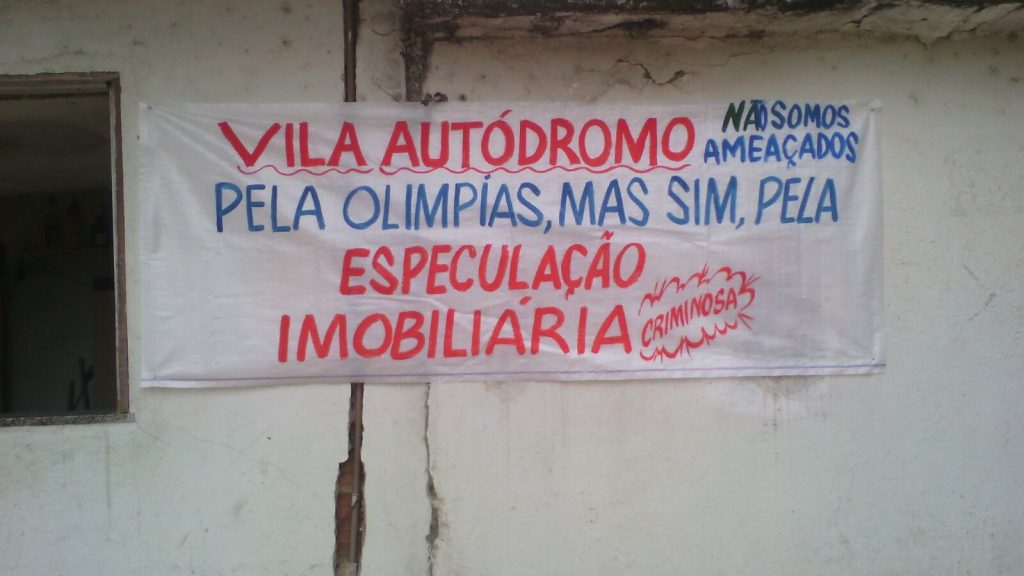

Further, residents remain unclear as to what will be built on the area close to the lagoon, where some houses still stand, waiting to be destroyed. Overlooking the Jacarepaguá Lagoon and directly next to the main Olympic Park, this land is valuable real estate. Residents regularly state that they do not (directly) blame the Olympics for their eviction. Instead the Olympics are used as a tool to evict them to allow real estate development on the land. This claim is strengthened by examining the list of donors to Mayor Eduardo Paes’ election campaigns, which includes major construction and real estate firms.

Notable among this list is Carlos Carvalho, who is unashamed of his desire to build a “city of the elite” with no space for the poor in Barra da Tijuca, the neighborhood where Vila Autódromo is located. He will be given some of the public land on which the Olympic Park sits after the Games, and will therefore be responsible for securing the local legacy of the Games. His repeated statements to the media saying he wishes to exclude the poor, coupled with his sizable donations to Eduardo Paes’ political campaigns suggests he has plans to extend his “city of the elite” onto the land vacated by Vila Autódromo.

Many of those who didn’t want to leave were unfairly excluded from this arrangement by the city. Heloisa Helena Costa Berto, for example, left her home when it was excluded from the rest of the community inside the Olympic Park, although she and her children returned daily to check on the house, which was also her Candomblé spiritual center. During this time, she started negotiating to sell her house, planning to rebuild closer to the heart of the community, where she would be able to stay. Because she had started to negotiate with the city, she was excluded from the deal for the new homes. By excluding Heloisa Helena and others in a similar position, the City has maximized the amount of land it can take from the residents under the guise of Olympic development.

It seems however, that in the face of the strong, impassioned resistance to eviction displayed by Vila Autódromo that resulted in those final families unwavering while the courts denied permission for removals, Mayor Paes and his real estate associates were required to accept they might end up with the site still looking like a war zone come August if they did not build housing on the site for the remaining residents.

As a result, the mayor shifted to a new strategy, that of building new housing to clean up the site for the Games. The only building that will stay in the community is the Catholic church, which the City says “isn’t a risk.” By removing residents from their traditional favela housing, which in Vila Autódromo’s case was rather large and well built, but which now are surrounded by rubble, the media and IOC dignitaries that will occupy the nearby buildings during the Olympic Games can remain blissfully unaware that there was once a favela on their doorstep. However, the poor quality housing and reduced space, coupled with the lofty interests of next-door real estate developers, will remain problematic for residents long after the Games have moved on.

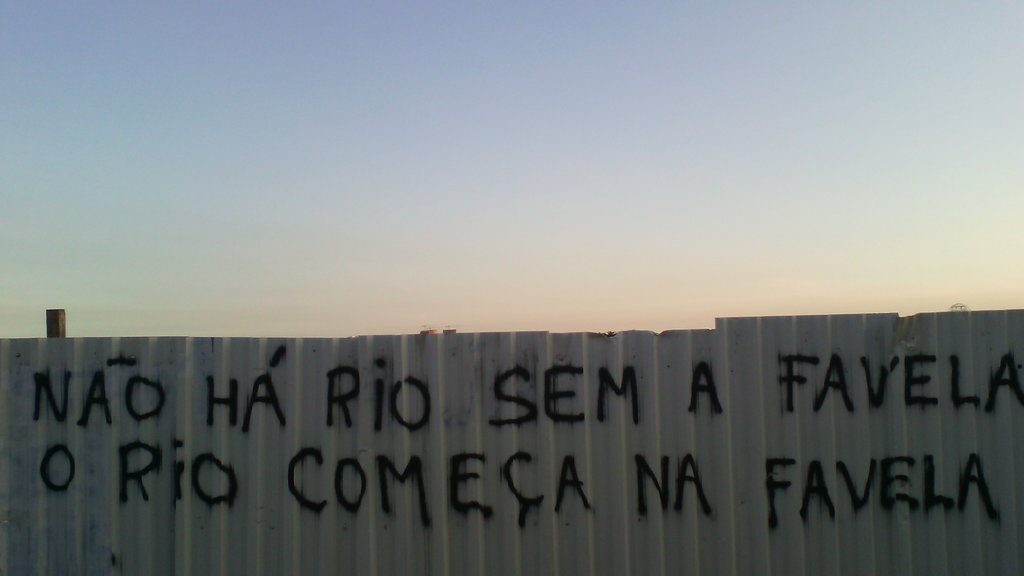

This erasing of favelas from Rio’s Olympics is deeply problematic. To only show Christ the Redeemer, Sugarloaf Mountain and Copacabana beach, as TV coverage of the Games undoubtedly will, conveys a skewed view of Rio’s reality. As the graffiti in Vila Autódromo asserts “there is no Rio without the favela,” and the City’s move to hide the favela origins of Vila Autódromo amounts to an abandonment of the government’s duty to govern for all. As resident Sandra Maria said after the Neighborhood Association was destroyed, “poverty exists here and everyone knows it. If you don’t want to show poverty to the world, end poverty!” It would be good if the next Mayor of Rio, due to be elected in October, embraced this slogan, and developed policy solutions that will involve and empower residents, for the benefit of all. As it stands however, Rio’s Olympic Games have been used by the City to exclude and disempower hundreds of thousands of Rio’s favela residents.

Adam Talbot is a doctoral researcher at the Centre of Sport, Tourism and Leisure Studies at the University of Brighton, UK. He is undertaking an ethnographic project focusing on social movements and activism at the Rio 2016 Olympic Games.